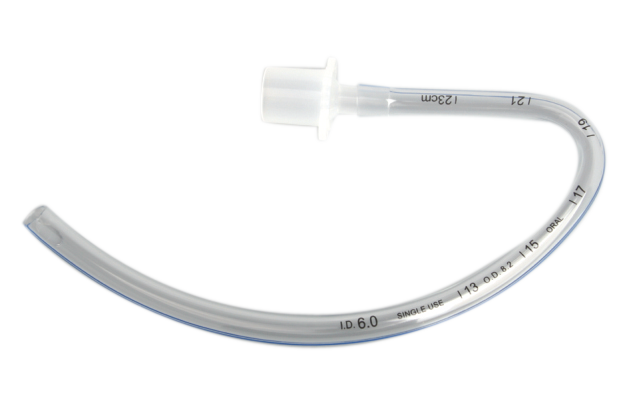

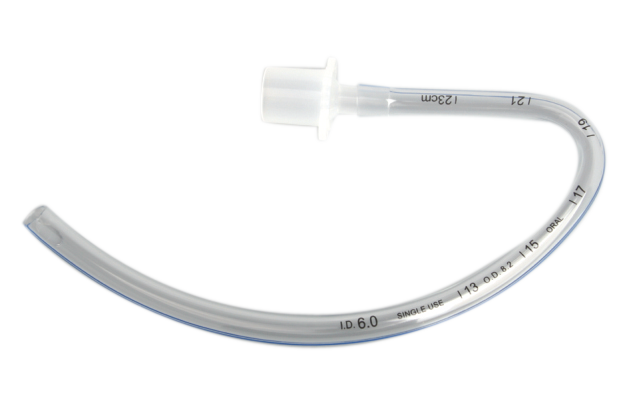

Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube, Uncuffed

Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube, Uncuffed

airway management is the process of ensuring that a patient's respiratory tract is open and unobstructed so that they can breathe properly. One part of airway management is the use of tracheal tubes, which are inserted into the trachea (windpipe) in order to keep the airway open. This article will focus on one type of tracheal tube, the oral preformed tracheal tube, which is inserted through the mouth.

Description

- Be used of oral intubation

- Responsive pilot balloons.

- Bull-nose tips.

- Split-resistant radiopaque lines.

- Smooth Murphy eye.

- Kink-resistant thermosensitive tubes.

| Ref. No.: |

Size: |

Qty. Cs: |

| NMR100630 |

3.0 |

100 |

| NMR100635 |

3.5 |

100 |

| NMR100640 |

4.0 |

100 |

| NMR100645 |

4.5 |

100 |

| NMR100650 |

5.0 |

100 |

| NMR100655 |

5.5 |

100 |

| NMR100660 |

6.0 |

100 |

| NMR100665 |

6.5 |

100 |

| NMR100670 |

7.0 |

100 |

| NMR100675 |

7.5 |

100 |

| NMR100680 |

8.0 |

100 |

| NMR100585 |

8.5 |

100 |

| NMR100690 |

9.0 |

100 |

| NMR100695 |

9.5 |

100 |

| NMR100610 |

10.0 |

100 |

Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube, Uncuffed

airway management is the process of ensuring that a patient's respiratory tract is open and unobstructed so that they can breathe properly. One part of airway management is the use of tracheal tubes, which are inserted into the trachea (windpipe) in order to keep the airway open. This article will focus on one type of tracheal tube, the oral preformed tracheal tube, which is inserted through the mouth.

What is an Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube?

An oral preformed tracheal tube, also known as a laryngeal mask airway (LMA), is a device that is inserted into the patient's mouth and then down their throat in order to provide a direct airway. This type of tube is most commonly used in emergency situations when time is of the essence and the patient cannot be intubated orally or through the nose. LMAs are also used for short-term procedures such as bronchoscopies.

The Different Types of Oral Preformed Tracheal Tubes

There are many different types of oral preformed tracheal tubes available on the market, and it can be difficult to know which one is right for you. In this blog post, we'll take a look at the different types of oral preformed tracheal tubes and their features, so that you can make an informed decision about which type is right for you.

The most common type of oral preformed tracheal tube is the cuffed tube. Cuffed tubes have a balloon-like cuff around the outside of the tube, which helps to seal the airway and prevent air from leaking around the tube. uncuffed tubes do not have this cuff, and may be more comfortable for some patients.

Another feature to consider is the size of the tube. Oral preformed tracheal tubes are available in a variety of sizes, from very small (for infants and children) to larger sizes for adults. The size of the tube you need will depend on your individual anatomy.

Finally, you'll need to decide whether you want a disposable or reusable tube. Disposable tubes are single-use only and must be thrown away after use. Reusable tubes can be used multiple times and are often less

Pros and Cons of an Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube

There are many different types of tracheal tubes available on the market today, and each has its own set of pros and cons. One type of tracheal tube that is gaining popularity is the oral preformed tracheal tube, or OPTT. Here, we will take a look at some of the pros and cons of using an OPTT.

One major pro of using an OPTT is that it can be inserted quickly and easily. This is due to the fact that the tube is pre-formed, so it does not require any manipulation once it is in place. This can be a major advantage in emergency situations where time is of the essence.

Another advantage of using an OPTT is that it provides a good seal. The fact that the tube is pre-formed means that it will fit snugly against the walls of the trachea, which helps to prevent leakage. Additionally, the cuff on an OPTT can be inflated to provide an even better seal.

There are a few potential disadvantages to using an OPTT as well. One is that because the tube is pre-formed, it may not fit all patients properly. This could lead to complications if the tube does not fit securely

What are the Best Practices for Using an Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube?

When it comes to using an oral preformed tracheal tube, there are certain best practices that should be followed in order to ensure a safe and successful procedure. Here are some tips to keep in mind:

1. Make sure the patient is properly positioned. The head should be in a neutral position and the neck should be extended. This will help ensure that the tube is placed in the correct location.

2. Use a size appropriate for the patient. The tube should be sized based on the patient's height and weight.

3. Insert the tube slowly and carefully. Take your time to insert the tube and be careful not to damage the patient's airway or cause them any discomfort.

4. Secure the tube in place once it has been inserted. Use tape or other means to secure the tube so that it does not move around during the procedure.

5. Monitor the patient closely after the procedure. Make sure to monitor vital signs and look for any signs of distress or complications.

How to Care for an Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube

If you or a loved one has been recently fitted with an oral preformed tracheal tube (OPTT), it is important to know how to properly care for the device. Here are some tips on how to keep your OPTT clean and in good working condition.

1. Rinse the tube with warm water after each use.

2. Clean the tube with a mild soap and water solution at least once a day.

3. Inspect the tube regularly for any cracks, leaks or other damage.

4. If the tube becomes damaged, contact your healthcare provider immediately.

5. Keep the tube dry and free from dirt and debris when not in use.

By following these simple care instructions, you can help ensure that your OPTT will provide you with many years of reliable service.

Conclusion

If you are considering oral preformed tracheal tubes, UNCUFFED may be the right choice for you. These tubes are designed to provide superior airway management and can be used in a variety of settings. With UNCUFFED, you can expect improved patient outcomes and a safer overall experience.

Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube- Uncuffed products available at low cost Nexgen Medical Online store, Be used for oral intubationResponsive pilot balloons, Bull-nose tips, Split-resistant radiopaque lines, Smooth Murphy eye, Kink-resistant thermosensitive tubes For more info visit Company website URL Nexgen Medical.

Oral

Preformed Tracheal Tube The aim of this study is to compare endotracheal tube leak, tube selection, mechanical ventilation, and side effects in the use of uncuffed tubes in both laparoscopic and laparotomy surgeries in pediatric patients.

Material and Method. Patients who underwent laparotomy (LT group) or laparoscopic (LS group) surgery between 1 and 60 months. In the selection of uncuffed tubes, it was also planned to start endotracheal intubation with the largest uncuffed tube and to start intubation with a small uncuffed tube if the tube encounters resistance and does not pass. Mechanical parameters, endotracheal tube size, tube changes, and side effects are recorded.

Results. A total of 102 patients, 38 females and 64 males, with a mean age of months, body weight

, and

height, were included. 54 patients underwent laparoscopic surgery, and 48 patients underwent laparotomy. Tube exchange was performed in a total of 18 patients. In patients who underwent tube exchange, 11 patients were intubated with a smaller ETT number and others endotracheal intubation; when the MV parameters were and

, a larger uncuffed tube was used due to PIP 30 cmH

2O pressure. Patients with aspiration were not found in the LT and LS groups. There was no difference in the intergroup evaluation for postoperative side effects such as cough, laryngospasm, stridor, and aspiration.

Conclusion. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of tube changes and side effects. So that we can start with the largest possible uncuffed tube to decrease ETT leak, both laparotomy and laparoscopic operations in children can be achieved with safe mechanical ventilation and target tidal volume.

1. Introduction

There is a widespread opinion that an uncuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) should be selected as the intubation tube in pediatric patients [

1–

4]. Despite disadvantages such as air leakage, environmental contamination of anesthetic gases, and aspiration, the application of an uncuffed ETT prevents trauma to the subglottic region in childhood; moreover, a lower airway is often preferred for many reasons, such as the application of resistance [

1,

2,

4,

5].

In addition, if the uncuffed ETT is not of a suitable size, the ETT leakage rate increases; this can create problems in reaching target tidal volumes in mechanical ventilation [

4,

6]. Therefore, to reduce the risk of aspiration in laparoscopic surgery, to prevent multiple laryngoscopies and intubations, and for more accurate monitoring of tidal volume and end-tidal carbon dioxide in ventilation, a cuffed ETT is also used [

1,

3]. However, the cricoid of the tracheal tubes poses a serious risk of airway damage in children due to the cuff being inserted between the subglottic region and the vocal cords and due to the fact that all pediatric cuffed tubes have the main design defects that can cause airway complications [

4,

6–

9].

Today, preference is given according to the advantages and disadvantages of ETT in pediatric patients; however, there are still no precise rules. In the literature, there are no reports of previous studies evaluating the use of cuffed vs. uncuffed ETT in pediatric patients under the age of 5 years in both laparotomy and laparoscopic surgeries. The aim of this investigation is to assess whether there is a relationship between the use of perioperative mechanical ventilation management and the frequency of development of complications.

2. Methods

Patients who underwent laparotomy (LT group) or laparoscopic (LS group) surgery between 1 and 60 months after receiving hospital ethics committee approval and who underwent uncuffed ETT during intubation were retrospectively included in the study. Patients with neuromuscular or congenital metabolic diseases of childhood, asthma and other lung diseases, intubation with a cuffed ETT, a difficult airway in a mask or intubation, postoperative intubation in the case of need, or tracheostomy were excluded from the study.

All patients received premedication with oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg at least 30 minutes before induction of general anesthesia. Intraoperative monitoring was provided with heart rate, noninvasive blood pressure, peripheral oxygen saturation, and capnography. The induction of general anesthesia was achieved with 5-8% sevoflurane (Sevorane®; Abbott Ltd., UK), 50% oxygen, 50% air, 1

μg/kg remifentanil (Rentanil®; Vem Ltd., Ankara, Turkey), and 0.45 mg/kg rocuronium bromide (Myocron®; Vem Ltd., Ankara, Turkey) in all children. The intubation was performed by the experienced anesthesiologist, who had >10 years of experience in pediatric anesthesia. The size of the uncuffed ETT (Chilecom®; Wellkang Ltd., London, UK) was formulated based on the internal diameter (ID) in mm: (Penlington’s formula). Tube selection was carried out so as to start endotracheal intubation with the largest uncuffed tube and continue intubation with a smaller uncuffed tube if the tube encountered resistance and could not pass. After the position of the tube was confirmed by auscultation, capnography, and

, tube detection was performed. After intubation, all patients underwent gastric decompression with a nasogastric tube followed by mechanical ventilation in pressure control ventilation (PCV) mode (Avance CS

2®; Datex Ohmeda, Madison WI, USA).

Respiration parameters such as end-tidal carbon dioxide (etCO

2), peak inspiratory pressure (PIP), inspiration tidal volume (TVi), and expiration tidal volume (TVe) of all preoperative and perioperative patients were measured through a flow sensor connected between the ETT and the ventilator circuit.

Mechanical ventilation (MV) settings were adjusted to PIP 10-30 cmH

2O, TVA 8-10 ml/kg, inspiration : expiration ratio 1 : 2, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) 5 cmH

2O. The number of inhalations was adjusted within the limits of etCO

2 25-40 mmHg. The value of the ETT leak was calculated [6,8]. A larger number tube size was decided by the attending anesthetist and was based on the existence of or or in the MV. Pneumoperitoneum was induced by insufflating carbon dioxide (CO

2) into the abdomen with the intra-abdominal pressure maintained at 10-11 mmHg (Electronic Endoflator; Karl-Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany), with the patient’s position recorded as flank, supine, lithotomy position, or 0-25° reverse Trendelenburg tilt. After pneumoperitoneum, TVe was adjusted to 8-10 ml/kg and etCO

2 to 25-40 mmHg, gradually increasing the values of PIP and respiration. After intraoperative or pneumoperitoneum and in the case of less than 8 ml/kg etCO

2 over 40 mmHg, manual ventilation was changed from PCV mode, and etCO

2 was reduced below 40 mmHg. In the maintenance of anesthesia, 4 l/min, 50% oxygen, and air, 2%-4% sevoflurane (MAC 1-1.3), and remifentanil 0.05-0.2

μg/kg/min were provided. The sexes of patients, age, body weight, height, ASA, operation, tube change, number of breaths, PIP, peripheral oxygen saturation (spO

2), respiratory count, etCO

2, duration of operation, additional drugs, ETT numbers, and tube changes were recorded. In addition, coughing, laryngospasm, or stridor at extubation was recorded. Demographic data, ventilation parameters (breath rate, PIP, and etCO

2), size of ETT, the reason for tube change, aspiration, coughing, laryngospasm, or stridor were recorded.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by using the SPSS 23 package program for Windows. While evaluating the study data, descriptive statistics were presented as mean and standard deviation. Comparison of quantitative data between groups was done by the Mann−Whitney test. Comparison of categorical variables between groups was done by the chi-squared test; continuous variables with a normal distribution were evaluated by using one-way analysis of variance, Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube while continuous variables with a nonnormal distribution were evaluated by using Kruskal-Wallis variance analysis. Statistical significance was evaluated at the level of

.

3. Results

A total of 102 patients, 38 females and 64 males, with a mean age of months, body weight

, and height

, Oral Preformed Tracheal Tube were included (Table 1). Surgical applications included acute abdominal surgery, ectopic testicle exploration, inguinal hernia repair, pyeloplasty, renal mass, colostomy opening or closing, and acute abdominal expression. Hirschsprung pull-through, Nissen fundoplication, liver biopsy, and cholangiography were used (Table 2)